Whatever water the Ijegba people drink, they should share with the rest of Nigeria—no, with all of Africa.

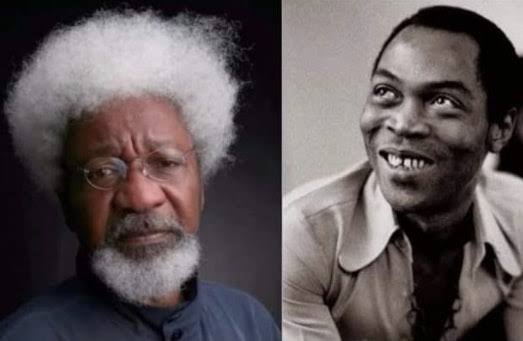

Ijegba (a blend of Ijebu and Egba)—a space defined roughly within a 50-by-50-mile radius—has produced some of the world’s brightest, most talented, and most activist characters: Wole Soyinka and Fela Kuti.

The former was rewarded with the Nobel Prize in 1986.

The latter received a Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award in 2026.

“Few people know that Fela and I are cousins,” Wole Soyinka said in 1979, when we brought Fela to Ile-Ife.

My friend, Moyo Ogundipe (an unsung hero—aka The First Ekiti Freak), visited my one-room apartment in 1979.

The apartment was given to me by Kole Omotoso, the celebrated author of JUST BEFORE DAWN—a book that so irked one former Nigerian head of state (whose name I won’t mention out of trepidation) that he not only banned it, but declared that any bookseller who dared to sell it would be made to smell their arsehole.

It wasn’t much of an apartment. It was part of Omotoso’s two-room boys’ quarters.

Femi Ifaturoti occupied the second room.

We named the area ESIALA REPUBLIC (from Eastern States Interim Assets and Liabilities Agency), because Femi and I pulled together and shared our assets and liabilities like a commune.

There I was, sitting down and minding my own problem jeje, when Ogundipe’s cool sports car parked in front of the boys’ quarters.

He brought his drink and smoke with him. He knew I was a starving artist without a kobo to my name.

“Mo,” Ogundipe said to me, “let’s blow their minds. I am the chairman of WNTV’s jamboree event called ‘TV Is Twenty.’ It is the 20th anniversary of the founding of the Western Nigerian Television. Awolowo, the visionary, founded the first television station in Africa in Ibadan in 1959—well before many European countries had television stations. It is now 20 years since then. We want to celebrate it with a bang. What do you suggest? Let’s blow their minds.”

Ogundipe was an executive producer at WNTV.

He took a sip from the brandy he brought with him and lit his cigarette, drawing it deeply into his lungs.

Under the influence of alcohol and a mind barely twenty years old, I said, “Let’s bring Fela to Ife! You will record the event for your television station, and you can play it every day for a month. Your viewers would love it!”

“Nah, Mo, calm down,” Ogundipe said. “First, we can’t get Fela. Second, I want a program that would take place in Ibadan, so people could come from Lagos to watch it.”

“You have the power and means to bring Fela,” I reminded him. “You are the executive producer for culture at the biggest television station in Africa. Fela needs you as much as you need him. If you bring Fela to Ife, people will come from Ibadan and Lagos to watch the program. Everybody is waiting for Fela’s next move. You have the megaphone to promote the event: constant adverts on your TV station.”

True, Fela was in trouble. He needed help.

He was broke, homeless, and under siege. He had just been allowed to return to Nigeria after the military regime banned him from the country.

They burned down his house, destroyed his nightclub and recording company, and during the raid threw his mother from the top storey of the building to the concrete ground floor—she later died in the hospital.

They beat Fela and his artists, reportedly leaving some of them dead.

Fela had several broken ribs. They threw him in jail without any charges—all because he released a song the authorities did not like.

His release from jail was conditional: he had to leave Nigeria.

He went into exile in Ghana.

Soyinka was also in exile in Ghana at the same time.

But Soyinka was allowed to return home after Professor Ojetunji Aboyade, the vice-chancellor of the University of Ife, appointed him professor of comparative literatures—after a long negotiation with the federal government, under the condition that the writer would ti ọwọ́ ọmọ rẹ̀ bọ aṣọ in Ile-Ife.

After a while, Fela—bored in Ghana—“sneaked” back into Lagos.

Of course, military security knew he was back, but they didn’t stop him.

They just kept watching him.

He was not working; he was recuperating and rehearsing new songs.

So, I said, “Baba Mo, you can do it.”

Femi Faturoti supported me. Ogundipe was voted out, 2 to 1.

“Okay, okay, guys—I will do it,” he agreed finally. “But I’m going to need a babanla poster for the event, Mo—and I need it by yesterday. I have a meeting with the director of WNTV on Tuesday. He will not approve Fela; he wants to keep his head down. But if I show him a mind-blowing poster that is already printed, and say it’s already in circulation, and the venue is already booked in Ife—and that I’ve already spent a lot of money, including an advance payment to Fela—he would feel unable to stop us.”

“Consider the poster done,” I told him. “Give me twenty-four hours to conceptualize and render it in pen—just black-and-white on paper, like an art drawing. You gerrit?”

“Good,” he said, getting up. “I must leave immediately. There’s a lot of work to do. You guys clean up the brandy. Sheriff (that is Femi), go tell the boys we are coming with Fela to Ife. Moyo, get me the poster.”

He left.

The rest is history.

Cars and buses from all over southern Nigeria—as far as Enugu, Benin City, and Port Harcourt—began arriving at the University of Ife campus by noon on the day of the Fela Festival.

Wole Soyinka was the chairman of the event. Kole Omotoso got us the venue—the amphitheater at Oduduwa Hall—for free.

The amphitheater was filled to the brim, with the audience screaming their heads off.

Soyinka—still not a Nobel laureate at the time—took the stage, cleared his throat, and the crowd went silent. You could hear a pin drop.

Soyinka began: “Ahem. Few people know that Fela and I are cousins from the same Ijegba villages. We also shared the same apartment in London. We shared many things in that apartment that I cannot tell you in public….”

Fela stopped him with: “One, two, three, four…” Then he began singing: “When trouble sleep, yanga go wake am—wetin e dey find ooooo….”

I was thinking, “You these Ijegba folks need to share with us the rivers from which you drink…,” as Fela’s music filled the air.

Attached is the poster that I produced for the event.